Published

Fri, Aug 4, 2023, 12:30

- Out this week, the book presents a social and political history of dance music in the UK.

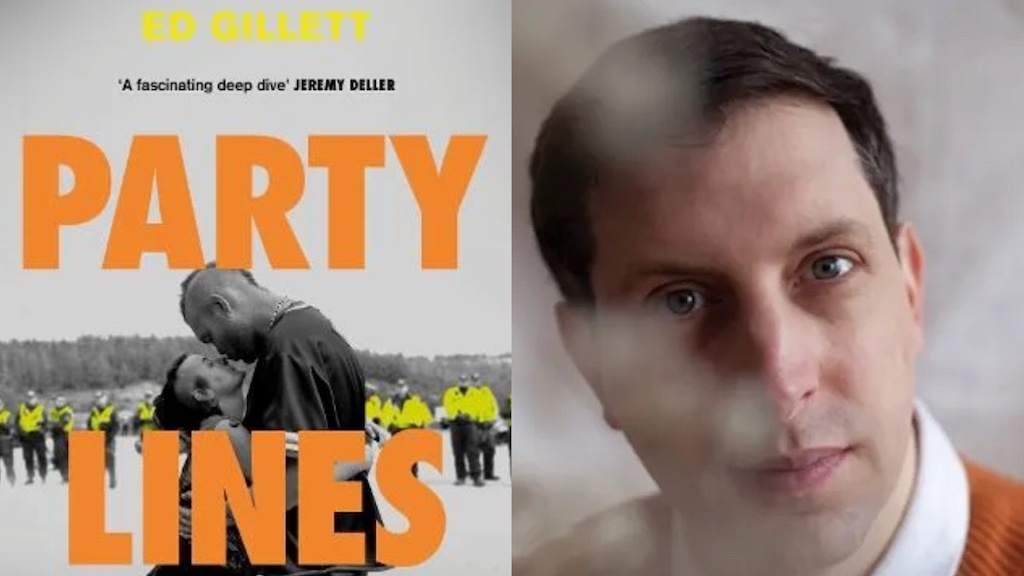

Earlier this week, we spoke with London-based writer Ed Gillett, whose first book, Party Lines: Dance Music and the Making of Modern Britain, is out now via Picador. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about your history with club culture and electronic music.

I've been a dance music fan for as long as I've been listening to music, way before I was aware of what clubs were or how they worked. Music and social history, politics and activism have been two parallel threads throughout my life. The third thread is a real interest in physical space. The Gillett family business has always been to do with property in the City of London. It was a big part of my upbringing, so when I started going clubbing to places like fabric and saw Smithfield Market starting up at 5 AM, I'd think about dance music's place in the lineage of industrial buildings, its use and reuse of spaces that were formerly something else.

The two things I hope really come across in the book are a real commitment to, and love for, the dance floor at its best. The way it can bring people together in ways that are radical or new, and offer different ways of thinking about the world. And then also a counterpart to that is a real critical eye for when the dance floor doesn't work like that.

What inspired Party Lines?

At the end of 2015, I wrote a piece looking back over the year of venue closures: Plastic People, The Astoria, Madame Jojo's etc. That was the first time I was able to combine my three areas of interest. I did a few more articles and then in 2018, I got the chance to work on Jeremy Deller's documentary Everybody in the Place, handling all the archive research. It really joined the dots for me in a historical sense and taught me that a lot of the conflicts and frictions I was interested in as a writer had been part of dance music since the beginning.

In terms of the book, I'm not blessed with lots of self-assurance, so it actually took someone else to suggest the idea. This happened during lockdown, after I wrote a viral piece for The Quietus on the tech house group Housekeeping. A literary agent reached out and asked if I'd ever considered putting all of my previous experience into a book. It was a real lightbulb moment.

What is Party Lines about?

It's a history of dance music focussed on its role in wider and social political conflicts over the past 50-odd years. The content of the book hasn't changed much since I wrote the proposal in 2020, but the emphasis has shifted slightly. I originally thought about it as a political history of dance music, extending beyond the eras covered in Matthew Collin's Altered State and Simon Reynolds' Energy Flash into the 2010s and beyond. As I was writing and researching, I realised this wasn't just a story about politics, social forces and culture affecting dance music, but that the reverse was also true. So it's also a dance music-y history of the UK.

For me, dance music is fundamentally about a power struggle. It represents in all its forms some kind of challenge to the status quo, a need to lose ourselves and dissolve into a broader kind of community and identity. And that instinctively throughout history has seemed to be a source of friction and tension among the establishment.

Can you give us some insight into the reporting and research process?

With Everybody in the Place, Jeremy Deller was adamant that he didn't want to focus on big-name DJs, and I carried that through to Party Lines. I think it's the right approach, particularly if you're interested in this culture as a lens through which to view wider conflicts. So relatively few of the people I spoke to or talk about are the most important DJs or artists of a given era. The one point where they intersect is with Spiral Tribe in the mid-'90s, though I didn't necessarily speak to them about their DJing.

Party Lines is a book with music at its heart, but it's not always strictly about the music. So the kind of research I was interested in was as likely to involve Freedom of Information (FOI) records or archives as going to raves or festivals. I took a couple of trips that make it into the book, such as Printworks in London or an illegal rave on a barge on the River Lea during lockdown. The latter was fun and fascinating and mildly ethically conflicting, although I was double vaccinated.

As the book progresses and it gets into the present, there's more in-person reporting, which wasn't necessarily deliberate. A lot of my my most exciting finds weren't in clubs but digging through Home Office archives and finding weird and wonderful things like police briefings on ecstasy or FOI information on how many people were fined for throwing illegal raves during lockdown.

How many interviews did you do?

Not a huge amount. There's at least one interview in every chapter and there's probably around 30 or 40 across the whole book.

How did you approach the writing process?

I think it's important to be transparent about these things. My advance was nowhere near large enough to cover the cost of writing the book. I got £10,000, which is very decent for a first-time author writing about a niche topic. I got £6,000 up front, minus tax and the cut my agent takes. I spent 18 months to two years writing, off and on. From beginning of 2021 to September 2022. And then a year of editing and finding photos.

I was working alongside it, freelancing on the odd TV project or doing corporate copywriting. I was also lucky to have built up some savings from my earlier career working in the charity sector, so that bridged the gap. I ended up burning through all of those. I was then just finding space in between to write the book. It was quite stop-start.

How much did your own tastes shape the book's narrative?

I tried to find a balance. I think it's important that the book has my voice in it and where there are things I'm not a fan of, I've not bitten my tongue. There are aspects of dance music I find exciting and interesting, and others I find creatively inert or politically suspect.

At the same time, there are plenty of aspects of dance music that aren't for me—either by design or by taste—which are still really important. I'm never going to have the same relationship to music and culture of Afro-diasporic origin as a Black British writer or listener would have. I've tried in the book to acknowledge and recognise that, and to not speak about that culture as if it's in any way mine, even though I love the music.

At other points, there's music I'm not as connected to aesthetically rather than socially. I've never been that into pounding nosebleed techno, but to not write about Spiral Tribe on that basis would be crazy. It's absolutely critical to the story.

Where do you see club culture headed?

Whether by mistake or design, a lot of the existing histories of dance music—Altered State, Energy Flash, the writings of Mark Fisher—end up feeling a little despondent about the present in which they're written. It's the idea that dance music was this new, exciting thing but everything now is a little more muted culturally.

I wanted Party Lines to be different. While I think dance music is facing unprecedented challenges, one of the key themes of the past ten to 15 years has been the broadening of acknowledgement of different experiences and a real return to dance music's roots in terms of the prominence and respect afforded to queer, Black, brown and other marginalised peoples.

Dance music has always been emergent. It's always had to operate at the fringes, to find space for itself in cultures that don't necessarily have its best interests at heart. And it's continued to thrive in those challenging environments. Dance music is a survivor, and I think that's a really beautiful thing.

If there's one thing I hope Party Lines will do is contribute to a wider understanding of the mechanics and history behind dance music. To help everyone think more carefully about their night out and how it fits into this wider history.