- Marco Polo wrote of spirit voices and phantom instruments and drums when crossing the Gobi. In the deserts of what is now southwest Jordan, an archeologist named Thomas became the revolutionary Lawrence of Arabia, leading Arabs in a revolt against German-allied Turks in WWI. Arid, clean, unforgiving, unadulterated...the desert has always been a mystical and inspiring place.

Are you worried that all of these vague notions of the importance of deserts to the human soul are simply an overblown way to intro a certain supposed counter-culture hippie-fest art rave involving some 40,000 N.P.O.D.s (Naked People On Drugs) known as Burning Man? Well, OK. But hang on a second. Whatever preconceived notions skeptics might have about the event, recent years have seen an influx of cutting-edge electronic music artists journeying out to the Black Rock Desert in Nevada where they've found either the perfect environment to perform, or spark their creative output when they got back home.

After all, what else could motivate two DJs from Hawaii's Asylum, Adam K and Willis Haltom, to take part in a giant sound camp known as Camp Tetrion, which showcased an enormous 40 foot tall Tetris game—projected and completely playable—and boasted the likes of Magda, Mathew Jonson, Konrad Black and Bill Patrick on their sound system? The entire camp was staged and shipped in a storage container from Hawaii. "We had 20,000 pounds of scaffolding, all in a 40' container, all of our personal stuff, lights, speakers, everything," recalls Adam, whose camp needed a week in the desert prior to the festival to set up their camp's sizable installations.

Photo credit: Michael Holden

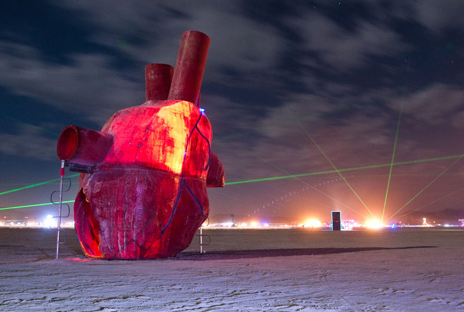

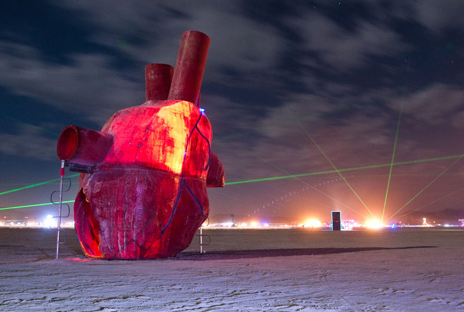

Burning Man takes place at the end of August, on the playa—or ancient dried lakebed—of prehistoric Lake Lahontan. At its peak 12,000 years ago, the Black Rock Desert sat 500' below the surface, but now, all that exists is the fine sediment of its alkali flats. And there is no moisture whatsoever. Combine that with the daytime heat, and the air literally whisks thoughts from your mind faster than the sweat on your brow. All that ancient alkali sediment, packed hard by the arid conditions, can be whipped up in apocalyptic dust devils and complete whiteout dust storms.

But the festival transforms this barren no-man's land into an adult Disneyworld. A mashup of Mad Max, Tron and Brigadoon. A magical kingdom of exploration, where the archaic and future meet in a supernova, creating a shining star called Black Rock City that only exists one week of the year (and in the process becomes the 5th largest city in Nevada). Still with me? OK, because here's where things get really interesting. There is nothing (save coffee and ice) for sale at Burning Man. In fact, there is no use for money, whatsoever; each participant brings everything they need for the week, and packs it out with them at the end. The use of motor vehicles are prohibited, unless they are licensed mutant vehicles, and these can take the form of anything, from a giant replica of the Golden Gate Bridge to a ground-shaking arachnid walker. (It should be noted that most of these art cars boast lights and sound systems that make most DJs salivate.)

Four-year veteran and global icon DJ Dan has seen his share of parties and big gigs, but there's still nothing more sacred than his yearly sabbatical to the desert. "When I first went there… the first set I ever had, I just looked out at everybody and realized there were no boundaries or borders of putting people in categories. I just looked at my CDs as an open playing field," Dan recalls. "I'm at a place where I can just go through my entire box of music and tell the story of what I'm feeling right now. And the feeling that the people give you at Burning Man, I swear, I need to go out here once a year to refill my soul so I can tell my story for the next year until I refill again."

Photo credit: Michael Holden

Burning Man takes place at the end of August, on the playa—or ancient dried lakebed—of prehistoric Lake Lahontan. At its peak 12,000 years ago, the Black Rock Desert sat 500' below the surface, but now, all that exists is the fine sediment of its alkali flats. And there is no moisture whatsoever. Combine that with the daytime heat, and the air literally whisks thoughts from your mind faster than the sweat on your brow. All that ancient alkali sediment, packed hard by the arid conditions, can be whipped up in apocalyptic dust devils and complete whiteout dust storms.

But the festival transforms this barren no-man's land into an adult Disneyworld. A mashup of Mad Max, Tron and Brigadoon. A magical kingdom of exploration, where the archaic and future meet in a supernova, creating a shining star called Black Rock City that only exists one week of the year (and in the process becomes the 5th largest city in Nevada). Still with me? OK, because here's where things get really interesting. There is nothing (save coffee and ice) for sale at Burning Man. In fact, there is no use for money, whatsoever; each participant brings everything they need for the week, and packs it out with them at the end. The use of motor vehicles are prohibited, unless they are licensed mutant vehicles, and these can take the form of anything, from a giant replica of the Golden Gate Bridge to a ground-shaking arachnid walker. (It should be noted that most of these art cars boast lights and sound systems that make most DJs salivate.)

Four-year veteran and global icon DJ Dan has seen his share of parties and big gigs, but there's still nothing more sacred than his yearly sabbatical to the desert. "When I first went there… the first set I ever had, I just looked out at everybody and realized there were no boundaries or borders of putting people in categories. I just looked at my CDs as an open playing field," Dan recalls. "I'm at a place where I can just go through my entire box of music and tell the story of what I'm feeling right now. And the feeling that the people give you at Burning Man, I swear, I need to go out here once a year to refill my soul so I can tell my story for the next year until I refill again."

Photo credit: Eric Spaceman

The particular event Dan recalls was a sunrise set at Opulent Temple (currently, one of the larger sound camps, distinctive for its big lineups, large projection screens, enclosed DJ booth and enough flamethrowers to clear Iwo Jima) when another DJ had no-showed. "I remember looking out and thinking to myself, that's not the way I would ever normally play … it sort of challenged me to open up and maybe express myself more than I usually would. You hear so many DJs say the same thing—they go out there and think they're going to play one thing, but they get out there and do something different."

Dan continues to explain what the festival means to him as a performer, lamenting the fact that becoming a successful touring DJ might give more opportunities to play, but still doesn't yield the ideal environment of complete artistic freedom. "[At Burning Man] it's like: 'No, there are no rules, this is your playground, you're four years old again, have a fucking blast,'" he laughs. Even an enthusiast like Dan knows how he sounds, though: "Every single person that is skeptical, that you try to tell and convince what is so special about it…almost feels like even telling them and even describing it, and even showing photos cheapens what it really is."

Speaking of skeptics, there were probably none bigger than notorious cool kids and techno stars Troy Pierce and Magda, who made their first trip to Burning Man this year. "I remember hearing about [Burning Man] for the first time when I lived in New York, maybe in like '97," recalls Pierce. "My best friend at the time was hanging out with this girl from San Francisco and she was super into it. This girl was the typical S.F. hippie-ish chick and her endorsement of the event forever tainted my interest in what I imagined to be a weeklong desert burnout in a dusty Hooverville where thousands of tie-dyed 'hemp' enthusiasts get stoned and braid each others hair." Magda's initial perceptions were roughly the same, as she describes her initial thoughts on Burning Man being a "big hippie festival, which is really cheesy and full of trance music." But over time, both had friends who attended and painted a different picture that eventually persuaded them to go.

Photo credit: Eric Spaceman

The particular event Dan recalls was a sunrise set at Opulent Temple (currently, one of the larger sound camps, distinctive for its big lineups, large projection screens, enclosed DJ booth and enough flamethrowers to clear Iwo Jima) when another DJ had no-showed. "I remember looking out and thinking to myself, that's not the way I would ever normally play … it sort of challenged me to open up and maybe express myself more than I usually would. You hear so many DJs say the same thing—they go out there and think they're going to play one thing, but they get out there and do something different."

Dan continues to explain what the festival means to him as a performer, lamenting the fact that becoming a successful touring DJ might give more opportunities to play, but still doesn't yield the ideal environment of complete artistic freedom. "[At Burning Man] it's like: 'No, there are no rules, this is your playground, you're four years old again, have a fucking blast,'" he laughs. Even an enthusiast like Dan knows how he sounds, though: "Every single person that is skeptical, that you try to tell and convince what is so special about it…almost feels like even telling them and even describing it, and even showing photos cheapens what it really is."

Speaking of skeptics, there were probably none bigger than notorious cool kids and techno stars Troy Pierce and Magda, who made their first trip to Burning Man this year. "I remember hearing about [Burning Man] for the first time when I lived in New York, maybe in like '97," recalls Pierce. "My best friend at the time was hanging out with this girl from San Francisco and she was super into it. This girl was the typical S.F. hippie-ish chick and her endorsement of the event forever tainted my interest in what I imagined to be a weeklong desert burnout in a dusty Hooverville where thousands of tie-dyed 'hemp' enthusiasts get stoned and braid each others hair." Magda's initial perceptions were roughly the same, as she describes her initial thoughts on Burning Man being a "big hippie festival, which is really cheesy and full of trance music." But over time, both had friends who attended and painted a different picture that eventually persuaded them to go.

Photo credit: Neil Girling

Upon arriving amongst the chaos and dust, Magda celebrated her birthday on one of her first nights on the playa. "Me and Troy and a couple friends went out into the desert at night and set up a little bar, and we're watching this whole city from afar, and we couldn't believe it," she giggles. "There's an amoeba going by, or a Golden Gate Bridge, and then a plane, and the wagon from the 20's … it was unreal, like a sci-fi film, basically… it was a light show of craziness, just for us!"

Performing in the desert presented the duo with some challenges, however. Pierce used a borrowed computer, leaving a lot of his gear behind. Magda, meanwhile, experienced a common phenomenon known as "playa time," which is generally caused by days-upon-days of over-excitement, lack of sleep and complete loss of time. Asleep in a camper across the desert from her scheduled appearance at Camp Tetrion, she was awoken by a friend who convinced her that she needed to get up and play. But how was she going to get clear across the desert to DJ—in her pajamas no less? "There's a car outside waiting for you," her friend informed her. "We go outside, and [the car is] a giant grasshopper vehicle with, like, 20 people onboard, all lit up in neon," she laughed. "Pass the tequila!"

On the topic of returning, Piece says "without a doubt," and Magda contemplates the possibilities of planning her own camp, and even giving performing under the desert conditions another shot. But for every artist that goes, there is a different motivation. "Playing at Burning Man is the least of my interests," Mathew Jonson states matter-of-factly. "Obviously I would brings CDs to play and have fun, but it's not about the big stages for me, at all," he says gruffly, saying he spent most of his time riding around the festival's vast perimeter on his bike, exploring with friends and looking at the art installations.

Photo credit: Neil Girling

Upon arriving amongst the chaos and dust, Magda celebrated her birthday on one of her first nights on the playa. "Me and Troy and a couple friends went out into the desert at night and set up a little bar, and we're watching this whole city from afar, and we couldn't believe it," she giggles. "There's an amoeba going by, or a Golden Gate Bridge, and then a plane, and the wagon from the 20's … it was unreal, like a sci-fi film, basically… it was a light show of craziness, just for us!"

Performing in the desert presented the duo with some challenges, however. Pierce used a borrowed computer, leaving a lot of his gear behind. Magda, meanwhile, experienced a common phenomenon known as "playa time," which is generally caused by days-upon-days of over-excitement, lack of sleep and complete loss of time. Asleep in a camper across the desert from her scheduled appearance at Camp Tetrion, she was awoken by a friend who convinced her that she needed to get up and play. But how was she going to get clear across the desert to DJ—in her pajamas no less? "There's a car outside waiting for you," her friend informed her. "We go outside, and [the car is] a giant grasshopper vehicle with, like, 20 people onboard, all lit up in neon," she laughed. "Pass the tequila!"

On the topic of returning, Piece says "without a doubt," and Magda contemplates the possibilities of planning her own camp, and even giving performing under the desert conditions another shot. But for every artist that goes, there is a different motivation. "Playing at Burning Man is the least of my interests," Mathew Jonson states matter-of-factly. "Obviously I would brings CDs to play and have fun, but it's not about the big stages for me, at all," he says gruffly, saying he spent most of his time riding around the festival's vast perimeter on his bike, exploring with friends and looking at the art installations.

Photo credit: Lara604

Jonson had returned to Burning Man this past year after taking a few years off, and quite honestly, sounded turned off by questions about the event. But as we talked more about the affect the festival has on his artistry, he lights up immediately. "The inspiration that I get from going out there is like nothing else. It's so incredibly inspiring to see that many artists of all different kinds putting their heads together and doing such a wide variety of things. As an artist, it's the best thing I could do for myself to get inspired to write music." Speaking rapidly and excitedly, he pauses for a breath. "And also, all the different sounds that you get, not just from the stages at all—just from all the cars going around, and the noises the art is making, is very inspiring."

To wit: After attending the 2003 festival, Jonson took all the sounds he heard in the desert and created "Decompression," which was released on Minus the next year and has sold more than any of his other releases. "You know the blinky, kind of sparkly sounds on top?" he asks. "It sounds like an art car going by... All those sounds," he laughs more, giggling. "It's fucking awesome out there." By now, Jonson has no interest talking music, but rather, of the alternate society created out in the desert. "You go out there, everybody is giving everything to everybody, it's all about taking care of everyone else and sharing. That's what's so hard to come back to," he explains. "You come back into a reality where you expect to walk into a store and have the person offer you their whole house, you know?" (Burners commonly refer to the reality shock experienced upon re-entry into the real or "default" world as "decompression.")

Traditionally, the majority dance music at Burning Man has been reflected in the open air-friendly sounds of breaks and trance, but in recent years ethno-centric DJs like LA's David Starfire, Chicago's Radiohiro and Burning Man's reigning crown prince Bassnectar have all managed to turn their work there into a relative amount of stardom. This past year, the slow reverberations of dubstep seemed on the rise as well, especially past sunrise, when Black Rock City's insomniac contingent were still up but unable to move to higher BPMs.

Photo credit: Lara604

Jonson had returned to Burning Man this past year after taking a few years off, and quite honestly, sounded turned off by questions about the event. But as we talked more about the affect the festival has on his artistry, he lights up immediately. "The inspiration that I get from going out there is like nothing else. It's so incredibly inspiring to see that many artists of all different kinds putting their heads together and doing such a wide variety of things. As an artist, it's the best thing I could do for myself to get inspired to write music." Speaking rapidly and excitedly, he pauses for a breath. "And also, all the different sounds that you get, not just from the stages at all—just from all the cars going around, and the noises the art is making, is very inspiring."

To wit: After attending the 2003 festival, Jonson took all the sounds he heard in the desert and created "Decompression," which was released on Minus the next year and has sold more than any of his other releases. "You know the blinky, kind of sparkly sounds on top?" he asks. "It sounds like an art car going by... All those sounds," he laughs more, giggling. "It's fucking awesome out there." By now, Jonson has no interest talking music, but rather, of the alternate society created out in the desert. "You go out there, everybody is giving everything to everybody, it's all about taking care of everyone else and sharing. That's what's so hard to come back to," he explains. "You come back into a reality where you expect to walk into a store and have the person offer you their whole house, you know?" (Burners commonly refer to the reality shock experienced upon re-entry into the real or "default" world as "decompression.")

Traditionally, the majority dance music at Burning Man has been reflected in the open air-friendly sounds of breaks and trance, but in recent years ethno-centric DJs like LA's David Starfire, Chicago's Radiohiro and Burning Man's reigning crown prince Bassnectar have all managed to turn their work there into a relative amount of stardom. This past year, the slow reverberations of dubstep seemed on the rise as well, especially past sunrise, when Black Rock City's insomniac contingent were still up but unable to move to higher BPMs.

Photo credit: Scott Hess

If anyone is responsible for the changing face of electronic music at Burning Man, it's quite possibly New York's Wolf + Lamb, who first stumbled onto the playa in 2001 "like total fucking tourists with jeans and t-shirts—clueless, completely clueless," according to the duo's Zev Eisenberg. They'd return the next year, and feeling at home, the next year as well, this time with a sound system and friends. It was at that edition that they played a sunrise set inside Saul Melman and Ani Weinstein Johnny On The Spot art installation—a gigantic 40' homage to Marcel Duchamp's "Fountain."

"I think the first time we did a party [at Burning Man]—which was in that toilet, in that urinal all those years ago—we broke through, and we just had a night of sharing and love with everybody that was there, the 40, 50, 60 people that were streaming in, and once you play a sunrise out there, everything pales in comparison," he said from a road trip on the way back to New York. That night, as they played until dawn, they reached an epiphany. "We couldn't play any of that techno anymore—it was just too dark for the occasion," explained Eisenberg. "So Gadi [Mizrahi, the other half of Wolf + Lamb] started playing pop music for the next three hours. And when we got back to New York, we just started changing the whole sound of the label to a much more upbeat [style]… every year that we go back [to Burning Man], the music that we make the following year reflects our experiences out there."

Wolf + Lamb has never shied away from the affect the festival has on their music, which might seem odd considering the negative connotations still held by some within the music community. (On the topic of hippies, Eisenberg bristles. "Half the world won't come here because they think it's a hippie fest...really?") But in the end, the duo is proud to champion their greatest inspiration. "We don't want to push people to come out there, but we want people to know that pretty much any negative stigma they've heard about Burning Man was probably from someone who has never been there," he says. "And whenever they make it out there, we'll be waiting with good music."

There were many discussions about the implications of the festival on society at large, or perhaps the hope it instilled in participants. But for the DJs and artists, whether it was the stages to perform on, or the experiences that inspire, the very magic of Burning Man seems to be that it exists at all. Combining so many builders, engineers, artists, visionaries, thrill-seekers, crackpots, go-getters and psychonauts in one place might very well be the perfect super-saturated solution for the sounds you'll hear tomorrow. And if you—like many burners—remember your chemistry, you'll recall that all it takes is one grain of dust to crystallize that solution. And out there? It's very, very dusty.

Photo credit: Scott Hess

If anyone is responsible for the changing face of electronic music at Burning Man, it's quite possibly New York's Wolf + Lamb, who first stumbled onto the playa in 2001 "like total fucking tourists with jeans and t-shirts—clueless, completely clueless," according to the duo's Zev Eisenberg. They'd return the next year, and feeling at home, the next year as well, this time with a sound system and friends. It was at that edition that they played a sunrise set inside Saul Melman and Ani Weinstein Johnny On The Spot art installation—a gigantic 40' homage to Marcel Duchamp's "Fountain."

"I think the first time we did a party [at Burning Man]—which was in that toilet, in that urinal all those years ago—we broke through, and we just had a night of sharing and love with everybody that was there, the 40, 50, 60 people that were streaming in, and once you play a sunrise out there, everything pales in comparison," he said from a road trip on the way back to New York. That night, as they played until dawn, they reached an epiphany. "We couldn't play any of that techno anymore—it was just too dark for the occasion," explained Eisenberg. "So Gadi [Mizrahi, the other half of Wolf + Lamb] started playing pop music for the next three hours. And when we got back to New York, we just started changing the whole sound of the label to a much more upbeat [style]… every year that we go back [to Burning Man], the music that we make the following year reflects our experiences out there."

Wolf + Lamb has never shied away from the affect the festival has on their music, which might seem odd considering the negative connotations still held by some within the music community. (On the topic of hippies, Eisenberg bristles. "Half the world won't come here because they think it's a hippie fest...really?") But in the end, the duo is proud to champion their greatest inspiration. "We don't want to push people to come out there, but we want people to know that pretty much any negative stigma they've heard about Burning Man was probably from someone who has never been there," he says. "And whenever they make it out there, we'll be waiting with good music."

There were many discussions about the implications of the festival on society at large, or perhaps the hope it instilled in participants. But for the DJs and artists, whether it was the stages to perform on, or the experiences that inspire, the very magic of Burning Man seems to be that it exists at all. Combining so many builders, engineers, artists, visionaries, thrill-seekers, crackpots, go-getters and psychonauts in one place might very well be the perfect super-saturated solution for the sounds you'll hear tomorrow. And if you—like many burners—remember your chemistry, you'll recall that all it takes is one grain of dust to crystallize that solution. And out there? It's very, very dusty.

Photo credit: Michael Holden

Burning Man takes place at the end of August, on the playa—or ancient dried lakebed—of prehistoric Lake Lahontan. At its peak 12,000 years ago, the Black Rock Desert sat 500' below the surface, but now, all that exists is the fine sediment of its alkali flats. And there is no moisture whatsoever. Combine that with the daytime heat, and the air literally whisks thoughts from your mind faster than the sweat on your brow. All that ancient alkali sediment, packed hard by the arid conditions, can be whipped up in apocalyptic dust devils and complete whiteout dust storms.

But the festival transforms this barren no-man's land into an adult Disneyworld. A mashup of Mad Max, Tron and Brigadoon. A magical kingdom of exploration, where the archaic and future meet in a supernova, creating a shining star called Black Rock City that only exists one week of the year (and in the process becomes the 5th largest city in Nevada). Still with me? OK, because here's where things get really interesting. There is nothing (save coffee and ice) for sale at Burning Man. In fact, there is no use for money, whatsoever; each participant brings everything they need for the week, and packs it out with them at the end. The use of motor vehicles are prohibited, unless they are licensed mutant vehicles, and these can take the form of anything, from a giant replica of the Golden Gate Bridge to a ground-shaking arachnid walker. (It should be noted that most of these art cars boast lights and sound systems that make most DJs salivate.)

Four-year veteran and global icon DJ Dan has seen his share of parties and big gigs, but there's still nothing more sacred than his yearly sabbatical to the desert. "When I first went there… the first set I ever had, I just looked out at everybody and realized there were no boundaries or borders of putting people in categories. I just looked at my CDs as an open playing field," Dan recalls. "I'm at a place where I can just go through my entire box of music and tell the story of what I'm feeling right now. And the feeling that the people give you at Burning Man, I swear, I need to go out here once a year to refill my soul so I can tell my story for the next year until I refill again."

Photo credit: Michael Holden

Burning Man takes place at the end of August, on the playa—or ancient dried lakebed—of prehistoric Lake Lahontan. At its peak 12,000 years ago, the Black Rock Desert sat 500' below the surface, but now, all that exists is the fine sediment of its alkali flats. And there is no moisture whatsoever. Combine that with the daytime heat, and the air literally whisks thoughts from your mind faster than the sweat on your brow. All that ancient alkali sediment, packed hard by the arid conditions, can be whipped up in apocalyptic dust devils and complete whiteout dust storms.

But the festival transforms this barren no-man's land into an adult Disneyworld. A mashup of Mad Max, Tron and Brigadoon. A magical kingdom of exploration, where the archaic and future meet in a supernova, creating a shining star called Black Rock City that only exists one week of the year (and in the process becomes the 5th largest city in Nevada). Still with me? OK, because here's where things get really interesting. There is nothing (save coffee and ice) for sale at Burning Man. In fact, there is no use for money, whatsoever; each participant brings everything they need for the week, and packs it out with them at the end. The use of motor vehicles are prohibited, unless they are licensed mutant vehicles, and these can take the form of anything, from a giant replica of the Golden Gate Bridge to a ground-shaking arachnid walker. (It should be noted that most of these art cars boast lights and sound systems that make most DJs salivate.)

Four-year veteran and global icon DJ Dan has seen his share of parties and big gigs, but there's still nothing more sacred than his yearly sabbatical to the desert. "When I first went there… the first set I ever had, I just looked out at everybody and realized there were no boundaries or borders of putting people in categories. I just looked at my CDs as an open playing field," Dan recalls. "I'm at a place where I can just go through my entire box of music and tell the story of what I'm feeling right now. And the feeling that the people give you at Burning Man, I swear, I need to go out here once a year to refill my soul so I can tell my story for the next year until I refill again."

Photo credit: Eric Spaceman

The particular event Dan recalls was a sunrise set at Opulent Temple (currently, one of the larger sound camps, distinctive for its big lineups, large projection screens, enclosed DJ booth and enough flamethrowers to clear Iwo Jima) when another DJ had no-showed. "I remember looking out and thinking to myself, that's not the way I would ever normally play … it sort of challenged me to open up and maybe express myself more than I usually would. You hear so many DJs say the same thing—they go out there and think they're going to play one thing, but they get out there and do something different."

Dan continues to explain what the festival means to him as a performer, lamenting the fact that becoming a successful touring DJ might give more opportunities to play, but still doesn't yield the ideal environment of complete artistic freedom. "[At Burning Man] it's like: 'No, there are no rules, this is your playground, you're four years old again, have a fucking blast,'" he laughs. Even an enthusiast like Dan knows how he sounds, though: "Every single person that is skeptical, that you try to tell and convince what is so special about it…almost feels like even telling them and even describing it, and even showing photos cheapens what it really is."

Speaking of skeptics, there were probably none bigger than notorious cool kids and techno stars Troy Pierce and Magda, who made their first trip to Burning Man this year. "I remember hearing about [Burning Man] for the first time when I lived in New York, maybe in like '97," recalls Pierce. "My best friend at the time was hanging out with this girl from San Francisco and she was super into it. This girl was the typical S.F. hippie-ish chick and her endorsement of the event forever tainted my interest in what I imagined to be a weeklong desert burnout in a dusty Hooverville where thousands of tie-dyed 'hemp' enthusiasts get stoned and braid each others hair." Magda's initial perceptions were roughly the same, as she describes her initial thoughts on Burning Man being a "big hippie festival, which is really cheesy and full of trance music." But over time, both had friends who attended and painted a different picture that eventually persuaded them to go.

Photo credit: Eric Spaceman

The particular event Dan recalls was a sunrise set at Opulent Temple (currently, one of the larger sound camps, distinctive for its big lineups, large projection screens, enclosed DJ booth and enough flamethrowers to clear Iwo Jima) when another DJ had no-showed. "I remember looking out and thinking to myself, that's not the way I would ever normally play … it sort of challenged me to open up and maybe express myself more than I usually would. You hear so many DJs say the same thing—they go out there and think they're going to play one thing, but they get out there and do something different."

Dan continues to explain what the festival means to him as a performer, lamenting the fact that becoming a successful touring DJ might give more opportunities to play, but still doesn't yield the ideal environment of complete artistic freedom. "[At Burning Man] it's like: 'No, there are no rules, this is your playground, you're four years old again, have a fucking blast,'" he laughs. Even an enthusiast like Dan knows how he sounds, though: "Every single person that is skeptical, that you try to tell and convince what is so special about it…almost feels like even telling them and even describing it, and even showing photos cheapens what it really is."

Speaking of skeptics, there were probably none bigger than notorious cool kids and techno stars Troy Pierce and Magda, who made their first trip to Burning Man this year. "I remember hearing about [Burning Man] for the first time when I lived in New York, maybe in like '97," recalls Pierce. "My best friend at the time was hanging out with this girl from San Francisco and she was super into it. This girl was the typical S.F. hippie-ish chick and her endorsement of the event forever tainted my interest in what I imagined to be a weeklong desert burnout in a dusty Hooverville where thousands of tie-dyed 'hemp' enthusiasts get stoned and braid each others hair." Magda's initial perceptions were roughly the same, as she describes her initial thoughts on Burning Man being a "big hippie festival, which is really cheesy and full of trance music." But over time, both had friends who attended and painted a different picture that eventually persuaded them to go.

Photo credit: Neil Girling

Upon arriving amongst the chaos and dust, Magda celebrated her birthday on one of her first nights on the playa. "Me and Troy and a couple friends went out into the desert at night and set up a little bar, and we're watching this whole city from afar, and we couldn't believe it," she giggles. "There's an amoeba going by, or a Golden Gate Bridge, and then a plane, and the wagon from the 20's … it was unreal, like a sci-fi film, basically… it was a light show of craziness, just for us!"

Performing in the desert presented the duo with some challenges, however. Pierce used a borrowed computer, leaving a lot of his gear behind. Magda, meanwhile, experienced a common phenomenon known as "playa time," which is generally caused by days-upon-days of over-excitement, lack of sleep and complete loss of time. Asleep in a camper across the desert from her scheduled appearance at Camp Tetrion, she was awoken by a friend who convinced her that she needed to get up and play. But how was she going to get clear across the desert to DJ—in her pajamas no less? "There's a car outside waiting for you," her friend informed her. "We go outside, and [the car is] a giant grasshopper vehicle with, like, 20 people onboard, all lit up in neon," she laughed. "Pass the tequila!"

On the topic of returning, Piece says "without a doubt," and Magda contemplates the possibilities of planning her own camp, and even giving performing under the desert conditions another shot. But for every artist that goes, there is a different motivation. "Playing at Burning Man is the least of my interests," Mathew Jonson states matter-of-factly. "Obviously I would brings CDs to play and have fun, but it's not about the big stages for me, at all," he says gruffly, saying he spent most of his time riding around the festival's vast perimeter on his bike, exploring with friends and looking at the art installations.

Photo credit: Neil Girling

Upon arriving amongst the chaos and dust, Magda celebrated her birthday on one of her first nights on the playa. "Me and Troy and a couple friends went out into the desert at night and set up a little bar, and we're watching this whole city from afar, and we couldn't believe it," she giggles. "There's an amoeba going by, or a Golden Gate Bridge, and then a plane, and the wagon from the 20's … it was unreal, like a sci-fi film, basically… it was a light show of craziness, just for us!"

Performing in the desert presented the duo with some challenges, however. Pierce used a borrowed computer, leaving a lot of his gear behind. Magda, meanwhile, experienced a common phenomenon known as "playa time," which is generally caused by days-upon-days of over-excitement, lack of sleep and complete loss of time. Asleep in a camper across the desert from her scheduled appearance at Camp Tetrion, she was awoken by a friend who convinced her that she needed to get up and play. But how was she going to get clear across the desert to DJ—in her pajamas no less? "There's a car outside waiting for you," her friend informed her. "We go outside, and [the car is] a giant grasshopper vehicle with, like, 20 people onboard, all lit up in neon," she laughed. "Pass the tequila!"

On the topic of returning, Piece says "without a doubt," and Magda contemplates the possibilities of planning her own camp, and even giving performing under the desert conditions another shot. But for every artist that goes, there is a different motivation. "Playing at Burning Man is the least of my interests," Mathew Jonson states matter-of-factly. "Obviously I would brings CDs to play and have fun, but it's not about the big stages for me, at all," he says gruffly, saying he spent most of his time riding around the festival's vast perimeter on his bike, exploring with friends and looking at the art installations.

Photo credit: Lara604

Jonson had returned to Burning Man this past year after taking a few years off, and quite honestly, sounded turned off by questions about the event. But as we talked more about the affect the festival has on his artistry, he lights up immediately. "The inspiration that I get from going out there is like nothing else. It's so incredibly inspiring to see that many artists of all different kinds putting their heads together and doing such a wide variety of things. As an artist, it's the best thing I could do for myself to get inspired to write music." Speaking rapidly and excitedly, he pauses for a breath. "And also, all the different sounds that you get, not just from the stages at all—just from all the cars going around, and the noises the art is making, is very inspiring."

To wit: After attending the 2003 festival, Jonson took all the sounds he heard in the desert and created "Decompression," which was released on Minus the next year and has sold more than any of his other releases. "You know the blinky, kind of sparkly sounds on top?" he asks. "It sounds like an art car going by... All those sounds," he laughs more, giggling. "It's fucking awesome out there." By now, Jonson has no interest talking music, but rather, of the alternate society created out in the desert. "You go out there, everybody is giving everything to everybody, it's all about taking care of everyone else and sharing. That's what's so hard to come back to," he explains. "You come back into a reality where you expect to walk into a store and have the person offer you their whole house, you know?" (Burners commonly refer to the reality shock experienced upon re-entry into the real or "default" world as "decompression.")

Traditionally, the majority dance music at Burning Man has been reflected in the open air-friendly sounds of breaks and trance, but in recent years ethno-centric DJs like LA's David Starfire, Chicago's Radiohiro and Burning Man's reigning crown prince Bassnectar have all managed to turn their work there into a relative amount of stardom. This past year, the slow reverberations of dubstep seemed on the rise as well, especially past sunrise, when Black Rock City's insomniac contingent were still up but unable to move to higher BPMs.

Photo credit: Lara604

Jonson had returned to Burning Man this past year after taking a few years off, and quite honestly, sounded turned off by questions about the event. But as we talked more about the affect the festival has on his artistry, he lights up immediately. "The inspiration that I get from going out there is like nothing else. It's so incredibly inspiring to see that many artists of all different kinds putting their heads together and doing such a wide variety of things. As an artist, it's the best thing I could do for myself to get inspired to write music." Speaking rapidly and excitedly, he pauses for a breath. "And also, all the different sounds that you get, not just from the stages at all—just from all the cars going around, and the noises the art is making, is very inspiring."

To wit: After attending the 2003 festival, Jonson took all the sounds he heard in the desert and created "Decompression," which was released on Minus the next year and has sold more than any of his other releases. "You know the blinky, kind of sparkly sounds on top?" he asks. "It sounds like an art car going by... All those sounds," he laughs more, giggling. "It's fucking awesome out there." By now, Jonson has no interest talking music, but rather, of the alternate society created out in the desert. "You go out there, everybody is giving everything to everybody, it's all about taking care of everyone else and sharing. That's what's so hard to come back to," he explains. "You come back into a reality where you expect to walk into a store and have the person offer you their whole house, you know?" (Burners commonly refer to the reality shock experienced upon re-entry into the real or "default" world as "decompression.")

Traditionally, the majority dance music at Burning Man has been reflected in the open air-friendly sounds of breaks and trance, but in recent years ethno-centric DJs like LA's David Starfire, Chicago's Radiohiro and Burning Man's reigning crown prince Bassnectar have all managed to turn their work there into a relative amount of stardom. This past year, the slow reverberations of dubstep seemed on the rise as well, especially past sunrise, when Black Rock City's insomniac contingent were still up but unable to move to higher BPMs.

Photo credit: Scott Hess

If anyone is responsible for the changing face of electronic music at Burning Man, it's quite possibly New York's Wolf + Lamb, who first stumbled onto the playa in 2001 "like total fucking tourists with jeans and t-shirts—clueless, completely clueless," according to the duo's Zev Eisenberg. They'd return the next year, and feeling at home, the next year as well, this time with a sound system and friends. It was at that edition that they played a sunrise set inside Saul Melman and Ani Weinstein Johnny On The Spot art installation—a gigantic 40' homage to Marcel Duchamp's "Fountain."

"I think the first time we did a party [at Burning Man]—which was in that toilet, in that urinal all those years ago—we broke through, and we just had a night of sharing and love with everybody that was there, the 40, 50, 60 people that were streaming in, and once you play a sunrise out there, everything pales in comparison," he said from a road trip on the way back to New York. That night, as they played until dawn, they reached an epiphany. "We couldn't play any of that techno anymore—it was just too dark for the occasion," explained Eisenberg. "So Gadi [Mizrahi, the other half of Wolf + Lamb] started playing pop music for the next three hours. And when we got back to New York, we just started changing the whole sound of the label to a much more upbeat [style]… every year that we go back [to Burning Man], the music that we make the following year reflects our experiences out there."

Wolf + Lamb has never shied away from the affect the festival has on their music, which might seem odd considering the negative connotations still held by some within the music community. (On the topic of hippies, Eisenberg bristles. "Half the world won't come here because they think it's a hippie fest...really?") But in the end, the duo is proud to champion their greatest inspiration. "We don't want to push people to come out there, but we want people to know that pretty much any negative stigma they've heard about Burning Man was probably from someone who has never been there," he says. "And whenever they make it out there, we'll be waiting with good music."

There were many discussions about the implications of the festival on society at large, or perhaps the hope it instilled in participants. But for the DJs and artists, whether it was the stages to perform on, or the experiences that inspire, the very magic of Burning Man seems to be that it exists at all. Combining so many builders, engineers, artists, visionaries, thrill-seekers, crackpots, go-getters and psychonauts in one place might very well be the perfect super-saturated solution for the sounds you'll hear tomorrow. And if you—like many burners—remember your chemistry, you'll recall that all it takes is one grain of dust to crystallize that solution. And out there? It's very, very dusty.

Photo credit: Scott Hess

If anyone is responsible for the changing face of electronic music at Burning Man, it's quite possibly New York's Wolf + Lamb, who first stumbled onto the playa in 2001 "like total fucking tourists with jeans and t-shirts—clueless, completely clueless," according to the duo's Zev Eisenberg. They'd return the next year, and feeling at home, the next year as well, this time with a sound system and friends. It was at that edition that they played a sunrise set inside Saul Melman and Ani Weinstein Johnny On The Spot art installation—a gigantic 40' homage to Marcel Duchamp's "Fountain."

"I think the first time we did a party [at Burning Man]—which was in that toilet, in that urinal all those years ago—we broke through, and we just had a night of sharing and love with everybody that was there, the 40, 50, 60 people that were streaming in, and once you play a sunrise out there, everything pales in comparison," he said from a road trip on the way back to New York. That night, as they played until dawn, they reached an epiphany. "We couldn't play any of that techno anymore—it was just too dark for the occasion," explained Eisenberg. "So Gadi [Mizrahi, the other half of Wolf + Lamb] started playing pop music for the next three hours. And when we got back to New York, we just started changing the whole sound of the label to a much more upbeat [style]… every year that we go back [to Burning Man], the music that we make the following year reflects our experiences out there."

Wolf + Lamb has never shied away from the affect the festival has on their music, which might seem odd considering the negative connotations still held by some within the music community. (On the topic of hippies, Eisenberg bristles. "Half the world won't come here because they think it's a hippie fest...really?") But in the end, the duo is proud to champion their greatest inspiration. "We don't want to push people to come out there, but we want people to know that pretty much any negative stigma they've heard about Burning Man was probably from someone who has never been there," he says. "And whenever they make it out there, we'll be waiting with good music."

There were many discussions about the implications of the festival on society at large, or perhaps the hope it instilled in participants. But for the DJs and artists, whether it was the stages to perform on, or the experiences that inspire, the very magic of Burning Man seems to be that it exists at all. Combining so many builders, engineers, artists, visionaries, thrill-seekers, crackpots, go-getters and psychonauts in one place might very well be the perfect super-saturated solution for the sounds you'll hear tomorrow. And if you—like many burners—remember your chemistry, you'll recall that all it takes is one grain of dust to crystallize that solution. And out there? It's very, very dusty.