Published

Tue, Jan 29, 2013, 15:08

- RA's Jordan Rothlein visited the annual trade show this past weekend to get the scoop on the latest and greatest in music technology.

Each January, the National Association of Music Merchants converges on the Anaheim Convention Center for one of the industry's largest gatherings. And that means something very specific for the tech-minded. For us in electronic music, the NAMM Show invariably means new kit. That new synthesizer you've been salivating over? It was likely announced around the time of the show, and the convention center floor is typically the first place you can actually touch it.

But the show is simultaneously more and less than it seems. The electronic and production side of things is unquestionably a big draw, but as I wandered the enormous convention center halls this past weekend, I was struck by what a small fraction of the industry our interests represent. Carbon-fiber guitars, drum sets on slowly spinning platforms and vast plains of marching-band brass still took up much of the square footage this year. And NAMM attendees—all of whom must either be in the industry or attending at the invitation of a vendor—tend to match the stereotype of the aging hair metal veteran disturbingly well. Encouragingly, though, the folks crowded around controllers and plug-in demos looked younger and a good deal hipper, and I sensed no shortage of interest in the gear that keeps electronic music production spinning.

Of all the NAMM-synchronized rollouts this year, it was a trio of synthesizers that made the biggest splash. Korg has brought a classic back to the market with the MS-20 mini, now with USB-MIDI support and a desktop-friendly smaller footprint. Dave Smith Instruments introduced the Prophet 12, a polyphonic synth with a new sound engine, some gorgeous analog filters, a nifty display borrowed from their Tempest drum machine and admirably deep functionality. (At around $3000, it's a serious investment, though it sounds like a million bucks.)

Of all the NAMM-synchronized rollouts this year, it was a trio of synthesizers that made the biggest splash. Korg has brought a classic back to the market with the MS-20 mini, now with USB-MIDI support and a desktop-friendly smaller footprint. Dave Smith Instruments introduced the Prophet 12, a polyphonic synth with a new sound engine, some gorgeous analog filters, a nifty display borrowed from their Tempest drum machine and admirably deep functionality. (At around $3000, it's a serious investment, though it sounds like a million bucks.)

But it was Moog's entry, the Sub Phatty, that I found most impressive. Where previous Phattys sported digital readouts, the Sub Phatty is all knobs and analog circuitry. The synth, though, feels very much of the moment. Connect it to your computer via USB, and the Sub Phatty has the same functionality as your favorite soft-synths: you can automate all your knob-twiddles and play it with a MIDI track in your DAW. Its sound, of course, is one that software still can't deliver, though something in the bass tones I was teasing out at the Moog booth sounded supremely contemporary. It'll set you back around $1100 when it arrives in March, but it's money well spent for producers looking to step outside of the box without sacrificing what's appealing about working inside it.

There were a few conspicuous absences on the floor this year. Two of the biggest names in electronic music, Ableton and Native Instruments, didn't have booths. When I brought this up with one tech company rep, I was met with an incredulous look. Why would these companies waste time playing a game they obviously won some time ago? Nearly every DJ controller worth its salt was running NI's Traktor (or Serato, whose "booth" with hardware partner Rane was basically just a DJ performance space), and practically every computer not running Pro Tools was flexing Ableton Live. At its core, NAMM is about manufacturers convincing vendors to stock your stuff over everyone else's. These big three don't have any convincing left to do.

But it was Moog's entry, the Sub Phatty, that I found most impressive. Where previous Phattys sported digital readouts, the Sub Phatty is all knobs and analog circuitry. The synth, though, feels very much of the moment. Connect it to your computer via USB, and the Sub Phatty has the same functionality as your favorite soft-synths: you can automate all your knob-twiddles and play it with a MIDI track in your DAW. Its sound, of course, is one that software still can't deliver, though something in the bass tones I was teasing out at the Moog booth sounded supremely contemporary. It'll set you back around $1100 when it arrives in March, but it's money well spent for producers looking to step outside of the box without sacrificing what's appealing about working inside it.

There were a few conspicuous absences on the floor this year. Two of the biggest names in electronic music, Ableton and Native Instruments, didn't have booths. When I brought this up with one tech company rep, I was met with an incredulous look. Why would these companies waste time playing a game they obviously won some time ago? Nearly every DJ controller worth its salt was running NI's Traktor (or Serato, whose "booth" with hardware partner Rane was basically just a DJ performance space), and practically every computer not running Pro Tools was flexing Ableton Live. At its core, NAMM is about manufacturers convincing vendors to stock your stuff over everyone else's. These big three don't have any convincing left to do.

Which isn't to say these guys didn't show up: Ableton was an elevator ride from the convention floor in a hotel suite. (NI was, too, apparently, though I only found out about it after they'd packed up for the weekend.) There, Ableton reps were demoing the company's forthcoming Push controller. They floated Push back in the fall, but NAMM was one of the first chances for industry folks to see it in the flesh. It didn't disappoint. Far more than a mere reboot of the Ableton-centric APC40 controller, Push and its bank of 64 pads can launch clips, step-sequence and even compose melodies via a curious color-coded grid. The device certainly isn't without precedent, but it's exciting to think of something like this rolling out on a massive scale. At a trade show where "update" passes as "brand new," Push felt like a rather brave step forward. (And at a base price of $599, it stands to be a real game changer in the controller market.)

Ableton may have stayed upstairs, but Bitwig was working the floor as hard as possible. A studied Ableton competitor currently in beta, this new digital audio workstation is looking to improve upon a giant of electronic music production. With streamlined support for multiple displays, a mode that combines session and clip views in a single display and a novel feature for combining sound events within clips, it's clear where this Berlin-based startup has its sights set. We'll have to wait until later this year, when Bitwig emerges from the company's labs, to see how well they compete.

Which isn't to say these guys didn't show up: Ableton was an elevator ride from the convention floor in a hotel suite. (NI was, too, apparently, though I only found out about it after they'd packed up for the weekend.) There, Ableton reps were demoing the company's forthcoming Push controller. They floated Push back in the fall, but NAMM was one of the first chances for industry folks to see it in the flesh. It didn't disappoint. Far more than a mere reboot of the Ableton-centric APC40 controller, Push and its bank of 64 pads can launch clips, step-sequence and even compose melodies via a curious color-coded grid. The device certainly isn't without precedent, but it's exciting to think of something like this rolling out on a massive scale. At a trade show where "update" passes as "brand new," Push felt like a rather brave step forward. (And at a base price of $599, it stands to be a real game changer in the controller market.)

Ableton may have stayed upstairs, but Bitwig was working the floor as hard as possible. A studied Ableton competitor currently in beta, this new digital audio workstation is looking to improve upon a giant of electronic music production. With streamlined support for multiple displays, a mode that combines session and clip views in a single display and a novel feature for combining sound events within clips, it's clear where this Berlin-based startup has its sights set. We'll have to wait until later this year, when Bitwig emerges from the company's labs, to see how well they compete.

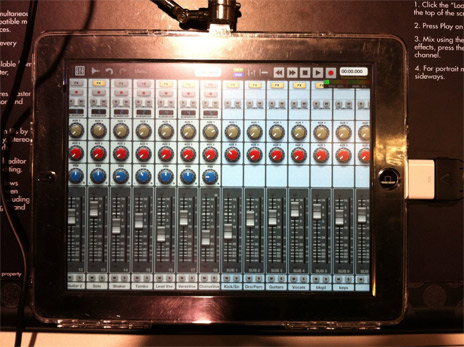

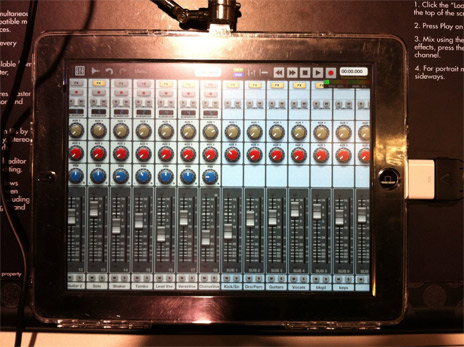

Whether running DJ software or powering standalone music-making apps, the iPad was ever-present at NAMM. The device is no longer a cheap thrill, but I sense the industry is still grappling with its implications for professionals. It came out last year, but WaveMachine Labs' Auria DAW remained the most unabashedly pro (and thoroughly badass) iPad app on the floor. Auria is a true 48-channel DAW, sporting high-res specs (24-bit/96 kHz recording on up to 24 tracks simultaneously) and a host of pro plug-ins from the likes of PSPaudioware. I still can't imagine tackling a major recording project on an iPad, but Auria (and the growing line of sophisticated iPad-ready audio interfaces from manufacturers like Focusrite and RME) suggests I start.

Whether running DJ software or powering standalone music-making apps, the iPad was ever-present at NAMM. The device is no longer a cheap thrill, but I sense the industry is still grappling with its implications for professionals. It came out last year, but WaveMachine Labs' Auria DAW remained the most unabashedly pro (and thoroughly badass) iPad app on the floor. Auria is a true 48-channel DAW, sporting high-res specs (24-bit/96 kHz recording on up to 24 tracks simultaneously) and a host of pro plug-ins from the likes of PSPaudioware. I still can't imagine tackling a major recording project on an iPad, but Auria (and the growing line of sophisticated iPad-ready audio interfaces from manufacturers like Focusrite and RME) suggests I start.

Another product that stands to "grow up" is the micro-keyboard, an invaluable tool for live performance. Keith McMillen Instruments seem to understand this better than most. After the crowdsourcing success story of QuNeo, KMI's pad controller that debuted at last year's NAMM, the company has brought the same level of quality hardware and smart design to a new micro-keyboard called QuNexus. At around $150, it's a solid $100 more expensive than its competitors, but it feels like a serious (and seriously durable) instrument by comparison. QuNexus' features (tilt- and location-sensitive keys, control voltage support for the modular freaks) further suggest it's in a class above its competitors. KMI also unveiled Rogue, a QuNeo attachment allows it to interface with your computer wirelessly at up to 60 meters. The execution is a touch awkward at this stage—it's nearly as thick as QuNeo itself and connects to the main device via a small USB cable—but it's certainly a start.

Another product that stands to "grow up" is the micro-keyboard, an invaluable tool for live performance. Keith McMillen Instruments seem to understand this better than most. After the crowdsourcing success story of QuNeo, KMI's pad controller that debuted at last year's NAMM, the company has brought the same level of quality hardware and smart design to a new micro-keyboard called QuNexus. At around $150, it's a solid $100 more expensive than its competitors, but it feels like a serious (and seriously durable) instrument by comparison. QuNexus' features (tilt- and location-sensitive keys, control voltage support for the modular freaks) further suggest it's in a class above its competitors. KMI also unveiled Rogue, a QuNeo attachment allows it to interface with your computer wirelessly at up to 60 meters. The execution is a touch awkward at this stage—it's nearly as thick as QuNeo itself and connects to the main device via a small USB cable—but it's certainly a start.

It's old hat now that everyone in America wants to be a DJ these days, and this assumption was evident on the floor at NAMM. From big names like Numark and Gemini to a handful of manufacturers I'd never heard of, everyone seemed to have a controller whose features and price had the consumer market in mind. Even Pioneer, a standard-bearer of the pro DJ market, has its eyes on this segment. At under $300, their DDJ-WeGo controller places more emphasis on its physical attributes (it comes in five colors! the lights underneath the jog dials pulse to the beat!) than its patently meager feature set. For Pioneer, though, a controller like this is less a prestige device than shrewd branding—a chance to capitalize on name recognition at a time when the DJs using their top-of-the-range devices have never been so visible in the United States.

In terms of those top-flight products, Pioneer continues to push its nexus system, which allows DJs to buck USB sticks and load tunes into CDJs direct from computers, smartphones and tablets over a Wi-Fi network. (Their Platinum Edition nexus bundle, comprising a pair of CDJ-2000s, a DJM-900 mixer with a Traktor-approved internal sound card and an external RMX-1000 effects unit, was the big new thing they were showing off this year.) Still a little unclear how this works, I asked a rep to run me through the process. nexus-enabled CDJs, it seems, need a hard connection to the wireless network, which struck me as surprisingly low-tech and clunky. Are there really that many clubs with a router in the DJ booth? The rep felt I was thinking about this the wrong way. Pioneer is taking the long view, he suggested, setting the stage for an era in which wireless networks would be ubiquitous in nightclubs.

It's old hat now that everyone in America wants to be a DJ these days, and this assumption was evident on the floor at NAMM. From big names like Numark and Gemini to a handful of manufacturers I'd never heard of, everyone seemed to have a controller whose features and price had the consumer market in mind. Even Pioneer, a standard-bearer of the pro DJ market, has its eyes on this segment. At under $300, their DDJ-WeGo controller places more emphasis on its physical attributes (it comes in five colors! the lights underneath the jog dials pulse to the beat!) than its patently meager feature set. For Pioneer, though, a controller like this is less a prestige device than shrewd branding—a chance to capitalize on name recognition at a time when the DJs using their top-of-the-range devices have never been so visible in the United States.

In terms of those top-flight products, Pioneer continues to push its nexus system, which allows DJs to buck USB sticks and load tunes into CDJs direct from computers, smartphones and tablets over a Wi-Fi network. (Their Platinum Edition nexus bundle, comprising a pair of CDJ-2000s, a DJM-900 mixer with a Traktor-approved internal sound card and an external RMX-1000 effects unit, was the big new thing they were showing off this year.) Still a little unclear how this works, I asked a rep to run me through the process. nexus-enabled CDJs, it seems, need a hard connection to the wireless network, which struck me as surprisingly low-tech and clunky. Are there really that many clubs with a router in the DJ booth? The rep felt I was thinking about this the wrong way. Pioneer is taking the long view, he suggested, setting the stage for an era in which wireless networks would be ubiquitous in nightclubs.

In the sea of controllers, the most original device I saw for DJs wasn't necessarily for DJs at all. The Vestax PBS-4, first announced in October, is aimed at web-streaming. It takes up to three channels of audio and four video inputs and some relatively simple controls for mixing audiovisual broadcasts. It looks like it was made with more complex broadcasting in mind, but I see this as a valuable tool for any DJ doing a lot of Ustreaming or an upstart looking to best Boiler Room.

In the sea of controllers, the most original device I saw for DJs wasn't necessarily for DJs at all. The Vestax PBS-4, first announced in October, is aimed at web-streaming. It takes up to three channels of audio and four video inputs and some relatively simple controls for mixing audiovisual broadcasts. It looks like it was made with more complex broadcasting in mind, but I see this as a valuable tool for any DJ doing a lot of Ustreaming or an upstart looking to best Boiler Room.

Of all the NAMM-synchronized rollouts this year, it was a trio of synthesizers that made the biggest splash. Korg has brought a classic back to the market with the MS-20 mini, now with USB-MIDI support and a desktop-friendly smaller footprint. Dave Smith Instruments introduced the Prophet 12, a polyphonic synth with a new sound engine, some gorgeous analog filters, a nifty display borrowed from their Tempest drum machine and admirably deep functionality. (At around $3000, it's a serious investment, though it sounds like a million bucks.)

Of all the NAMM-synchronized rollouts this year, it was a trio of synthesizers that made the biggest splash. Korg has brought a classic back to the market with the MS-20 mini, now with USB-MIDI support and a desktop-friendly smaller footprint. Dave Smith Instruments introduced the Prophet 12, a polyphonic synth with a new sound engine, some gorgeous analog filters, a nifty display borrowed from their Tempest drum machine and admirably deep functionality. (At around $3000, it's a serious investment, though it sounds like a million bucks.)

But it was Moog's entry, the Sub Phatty, that I found most impressive. Where previous Phattys sported digital readouts, the Sub Phatty is all knobs and analog circuitry. The synth, though, feels very much of the moment. Connect it to your computer via USB, and the Sub Phatty has the same functionality as your favorite soft-synths: you can automate all your knob-twiddles and play it with a MIDI track in your DAW. Its sound, of course, is one that software still can't deliver, though something in the bass tones I was teasing out at the Moog booth sounded supremely contemporary. It'll set you back around $1100 when it arrives in March, but it's money well spent for producers looking to step outside of the box without sacrificing what's appealing about working inside it.

There were a few conspicuous absences on the floor this year. Two of the biggest names in electronic music, Ableton and Native Instruments, didn't have booths. When I brought this up with one tech company rep, I was met with an incredulous look. Why would these companies waste time playing a game they obviously won some time ago? Nearly every DJ controller worth its salt was running NI's Traktor (or Serato, whose "booth" with hardware partner Rane was basically just a DJ performance space), and practically every computer not running Pro Tools was flexing Ableton Live. At its core, NAMM is about manufacturers convincing vendors to stock your stuff over everyone else's. These big three don't have any convincing left to do.

But it was Moog's entry, the Sub Phatty, that I found most impressive. Where previous Phattys sported digital readouts, the Sub Phatty is all knobs and analog circuitry. The synth, though, feels very much of the moment. Connect it to your computer via USB, and the Sub Phatty has the same functionality as your favorite soft-synths: you can automate all your knob-twiddles and play it with a MIDI track in your DAW. Its sound, of course, is one that software still can't deliver, though something in the bass tones I was teasing out at the Moog booth sounded supremely contemporary. It'll set you back around $1100 when it arrives in March, but it's money well spent for producers looking to step outside of the box without sacrificing what's appealing about working inside it.

There were a few conspicuous absences on the floor this year. Two of the biggest names in electronic music, Ableton and Native Instruments, didn't have booths. When I brought this up with one tech company rep, I was met with an incredulous look. Why would these companies waste time playing a game they obviously won some time ago? Nearly every DJ controller worth its salt was running NI's Traktor (or Serato, whose "booth" with hardware partner Rane was basically just a DJ performance space), and practically every computer not running Pro Tools was flexing Ableton Live. At its core, NAMM is about manufacturers convincing vendors to stock your stuff over everyone else's. These big three don't have any convincing left to do.

Which isn't to say these guys didn't show up: Ableton was an elevator ride from the convention floor in a hotel suite. (NI was, too, apparently, though I only found out about it after they'd packed up for the weekend.) There, Ableton reps were demoing the company's forthcoming Push controller. They floated Push back in the fall, but NAMM was one of the first chances for industry folks to see it in the flesh. It didn't disappoint. Far more than a mere reboot of the Ableton-centric APC40 controller, Push and its bank of 64 pads can launch clips, step-sequence and even compose melodies via a curious color-coded grid. The device certainly isn't without precedent, but it's exciting to think of something like this rolling out on a massive scale. At a trade show where "update" passes as "brand new," Push felt like a rather brave step forward. (And at a base price of $599, it stands to be a real game changer in the controller market.)

Ableton may have stayed upstairs, but Bitwig was working the floor as hard as possible. A studied Ableton competitor currently in beta, this new digital audio workstation is looking to improve upon a giant of electronic music production. With streamlined support for multiple displays, a mode that combines session and clip views in a single display and a novel feature for combining sound events within clips, it's clear where this Berlin-based startup has its sights set. We'll have to wait until later this year, when Bitwig emerges from the company's labs, to see how well they compete.

Which isn't to say these guys didn't show up: Ableton was an elevator ride from the convention floor in a hotel suite. (NI was, too, apparently, though I only found out about it after they'd packed up for the weekend.) There, Ableton reps were demoing the company's forthcoming Push controller. They floated Push back in the fall, but NAMM was one of the first chances for industry folks to see it in the flesh. It didn't disappoint. Far more than a mere reboot of the Ableton-centric APC40 controller, Push and its bank of 64 pads can launch clips, step-sequence and even compose melodies via a curious color-coded grid. The device certainly isn't without precedent, but it's exciting to think of something like this rolling out on a massive scale. At a trade show where "update" passes as "brand new," Push felt like a rather brave step forward. (And at a base price of $599, it stands to be a real game changer in the controller market.)

Ableton may have stayed upstairs, but Bitwig was working the floor as hard as possible. A studied Ableton competitor currently in beta, this new digital audio workstation is looking to improve upon a giant of electronic music production. With streamlined support for multiple displays, a mode that combines session and clip views in a single display and a novel feature for combining sound events within clips, it's clear where this Berlin-based startup has its sights set. We'll have to wait until later this year, when Bitwig emerges from the company's labs, to see how well they compete.

Whether running DJ software or powering standalone music-making apps, the iPad was ever-present at NAMM. The device is no longer a cheap thrill, but I sense the industry is still grappling with its implications for professionals. It came out last year, but WaveMachine Labs' Auria DAW remained the most unabashedly pro (and thoroughly badass) iPad app on the floor. Auria is a true 48-channel DAW, sporting high-res specs (24-bit/96 kHz recording on up to 24 tracks simultaneously) and a host of pro plug-ins from the likes of PSPaudioware. I still can't imagine tackling a major recording project on an iPad, but Auria (and the growing line of sophisticated iPad-ready audio interfaces from manufacturers like Focusrite and RME) suggests I start.

Whether running DJ software or powering standalone music-making apps, the iPad was ever-present at NAMM. The device is no longer a cheap thrill, but I sense the industry is still grappling with its implications for professionals. It came out last year, but WaveMachine Labs' Auria DAW remained the most unabashedly pro (and thoroughly badass) iPad app on the floor. Auria is a true 48-channel DAW, sporting high-res specs (24-bit/96 kHz recording on up to 24 tracks simultaneously) and a host of pro plug-ins from the likes of PSPaudioware. I still can't imagine tackling a major recording project on an iPad, but Auria (and the growing line of sophisticated iPad-ready audio interfaces from manufacturers like Focusrite and RME) suggests I start.

Another product that stands to "grow up" is the micro-keyboard, an invaluable tool for live performance. Keith McMillen Instruments seem to understand this better than most. After the crowdsourcing success story of QuNeo, KMI's pad controller that debuted at last year's NAMM, the company has brought the same level of quality hardware and smart design to a new micro-keyboard called QuNexus. At around $150, it's a solid $100 more expensive than its competitors, but it feels like a serious (and seriously durable) instrument by comparison. QuNexus' features (tilt- and location-sensitive keys, control voltage support for the modular freaks) further suggest it's in a class above its competitors. KMI also unveiled Rogue, a QuNeo attachment allows it to interface with your computer wirelessly at up to 60 meters. The execution is a touch awkward at this stage—it's nearly as thick as QuNeo itself and connects to the main device via a small USB cable—but it's certainly a start.

Another product that stands to "grow up" is the micro-keyboard, an invaluable tool for live performance. Keith McMillen Instruments seem to understand this better than most. After the crowdsourcing success story of QuNeo, KMI's pad controller that debuted at last year's NAMM, the company has brought the same level of quality hardware and smart design to a new micro-keyboard called QuNexus. At around $150, it's a solid $100 more expensive than its competitors, but it feels like a serious (and seriously durable) instrument by comparison. QuNexus' features (tilt- and location-sensitive keys, control voltage support for the modular freaks) further suggest it's in a class above its competitors. KMI also unveiled Rogue, a QuNeo attachment allows it to interface with your computer wirelessly at up to 60 meters. The execution is a touch awkward at this stage—it's nearly as thick as QuNeo itself and connects to the main device via a small USB cable—but it's certainly a start.

It's old hat now that everyone in America wants to be a DJ these days, and this assumption was evident on the floor at NAMM. From big names like Numark and Gemini to a handful of manufacturers I'd never heard of, everyone seemed to have a controller whose features and price had the consumer market in mind. Even Pioneer, a standard-bearer of the pro DJ market, has its eyes on this segment. At under $300, their DDJ-WeGo controller places more emphasis on its physical attributes (it comes in five colors! the lights underneath the jog dials pulse to the beat!) than its patently meager feature set. For Pioneer, though, a controller like this is less a prestige device than shrewd branding—a chance to capitalize on name recognition at a time when the DJs using their top-of-the-range devices have never been so visible in the United States.

In terms of those top-flight products, Pioneer continues to push its nexus system, which allows DJs to buck USB sticks and load tunes into CDJs direct from computers, smartphones and tablets over a Wi-Fi network. (Their Platinum Edition nexus bundle, comprising a pair of CDJ-2000s, a DJM-900 mixer with a Traktor-approved internal sound card and an external RMX-1000 effects unit, was the big new thing they were showing off this year.) Still a little unclear how this works, I asked a rep to run me through the process. nexus-enabled CDJs, it seems, need a hard connection to the wireless network, which struck me as surprisingly low-tech and clunky. Are there really that many clubs with a router in the DJ booth? The rep felt I was thinking about this the wrong way. Pioneer is taking the long view, he suggested, setting the stage for an era in which wireless networks would be ubiquitous in nightclubs.

It's old hat now that everyone in America wants to be a DJ these days, and this assumption was evident on the floor at NAMM. From big names like Numark and Gemini to a handful of manufacturers I'd never heard of, everyone seemed to have a controller whose features and price had the consumer market in mind. Even Pioneer, a standard-bearer of the pro DJ market, has its eyes on this segment. At under $300, their DDJ-WeGo controller places more emphasis on its physical attributes (it comes in five colors! the lights underneath the jog dials pulse to the beat!) than its patently meager feature set. For Pioneer, though, a controller like this is less a prestige device than shrewd branding—a chance to capitalize on name recognition at a time when the DJs using their top-of-the-range devices have never been so visible in the United States.

In terms of those top-flight products, Pioneer continues to push its nexus system, which allows DJs to buck USB sticks and load tunes into CDJs direct from computers, smartphones and tablets over a Wi-Fi network. (Their Platinum Edition nexus bundle, comprising a pair of CDJ-2000s, a DJM-900 mixer with a Traktor-approved internal sound card and an external RMX-1000 effects unit, was the big new thing they were showing off this year.) Still a little unclear how this works, I asked a rep to run me through the process. nexus-enabled CDJs, it seems, need a hard connection to the wireless network, which struck me as surprisingly low-tech and clunky. Are there really that many clubs with a router in the DJ booth? The rep felt I was thinking about this the wrong way. Pioneer is taking the long view, he suggested, setting the stage for an era in which wireless networks would be ubiquitous in nightclubs.

In the sea of controllers, the most original device I saw for DJs wasn't necessarily for DJs at all. The Vestax PBS-4, first announced in October, is aimed at web-streaming. It takes up to three channels of audio and four video inputs and some relatively simple controls for mixing audiovisual broadcasts. It looks like it was made with more complex broadcasting in mind, but I see this as a valuable tool for any DJ doing a lot of Ustreaming or an upstart looking to best Boiler Room.

In the sea of controllers, the most original device I saw for DJs wasn't necessarily for DJs at all. The Vestax PBS-4, first announced in October, is aimed at web-streaming. It takes up to three channels of audio and four video inputs and some relatively simple controls for mixing audiovisual broadcasts. It looks like it was made with more complex broadcasting in mind, but I see this as a valuable tool for any DJ doing a lot of Ustreaming or an upstart looking to best Boiler Room.